Deep dive into the 1 600-year odyssey of Hagia Sophia—perfect for history buffs and architecture lovers.

🎟️ BOOK YOUR ISTANBUL TOURS NOW! 🎟️

Online booking is easy and secure. Click the link below, choose your date, and confirm instantly:

⚠️ Don’t wait—these tours often sell out, especially on weekends and holidays!

1. The First “Great Church” Rises (c. 360 CE)

When Emperor Constantius II moved the imperial capital to Constantinople, he needed a cathedral to match Rome’s prestige. The result was the Megale Ekklesia (“Great Church”), a timber-roofed basilica measuring roughly 60 × 70 metres—vast for the 4th century. Its nave hosted gleaming marble columns imported from Asia Minor, while a gilded ciborium sheltered the altar.

Contemporary chroniclers claimed the light that filtered through its clerestory stood “like a crown” above worshippers, foreshadowing Hagia Sophia’s future reputation for ethereal luminosity. Unfortunately, the structure’s wooden super-structure made it vulnerable to both fire and political volatility.

2. Destruction in Riot & Rebuild (404 – 415 CE)

In 404 CE the banishment of fiery Patriarch John Chrysostom sparked riots. Flames engulfed the basilica and nearby Senate House. Emperor Theodosius II ordered an ambitious stone replacement, inaugurating it on 10 October 415 CE. This second Hagia Sophia featured a colonnaded atrium and a pitched wooden roof supported by 40 red-porphyry columns—symbols of imperial power.

Mosaics of peacocks, vines, and gold-backed crosses adorned the apse, and historians speak of a silver ambo (pulpit) so dazzling that it reflected candlelight across the marble floor like rippling water. Yet, as Constantinople’s population swelled, tensions simmered beneath the city’s glittering façade.

3. The Nika Revolt & Total Ruin (532 CE)

The Nika Revolt—a violent uprising against Justinian I—was the worst urban riot in Roman history. Blues and Greens united, chanting “Nika” (“Conquer!”), torching half the city, including Hagia Sophia.

Justinian contemplated fleeing, but Empress Theodora reputedly declared, “Purple makes a fine shroud.” He stayed, quashed the rebellion, and envisioned a basilica unlike any before: a monument to divine wisdom (Hagia Sophia translates literally to “Holy Wisdom”) and imperial resilience. This decision would give birth to the edifice recognized today.

4. Justinian’s Marvel Completed (537 CE)

Architects Anthemius of Tralles (a mathematician) and Isidore of Miletus (a physicist) fused a rectangular basilica with a colossal 31-metre-diameter dome suspended on pendentives—an engineering leap that birthed the Byzantine architectural style. Justinian allegedly proclaimed, “Solomon, I have surpassed thee!” when he first entered on 27 December 537 CE.

Twenty-two years’ worth of Mediterranean taxes financed marble from Proconnesus, green Thasos, and purple Phrygian quarries, while 40 000 pounds of silver plated the ambo, doors, and screen. More than a building, it embodied the political theology of the empire: Rome’s might fused with Christian cosmology.

5. Dome Collapse & Reinvention (558 – 562 CE)

An earthquake on 7 May 558 CE shattered the main dome, sending mosaic tesserae raining onto the sanctuary. Justinian recalled Isidore the Younger, who raised the crown by 6 metres and reshaped its curvature, distributing weight more evenly to the four massive piers.

He also replaced the formerly flat east and west tympana with arched windows, creating the famous “floating” illusion of a ring of light under the dome. By 562 CE Hagia Sophia re-opened stronger, brighter, and acoustically enhanced—its echo lasting nearly 12 seconds, perfect for Byzantine chant.

6. Crusader Control—Catholic Cathedral (1204 – 1261 CE)

The Fourth Crusade diverted to Constantinople, sacking the city on 13 April 1204. Latin knights enthroned Baldwin I as emperor and re-dedicated Hagia Sophia to Roman Catholic worship. Relics, including the “mantle of the Virgin” and pieces of the True Cross, were shipped to Venice and Paris, stripping the basilica of sacred prestige.

French canon Robert of Clari marveled that “one could scarcely see the walls for all the gold and silver.” Yet greedy occupiers melted many fittings into coin, leaving the church structurally sound but spiritually ransacked.

7. Byzantine Restoration (1261 CE)

When Michael VIII Palaiologos reclaimed Constantinople, the Orthodox clergy staged a triumphant liturgy in Hagia Sophia on 15 August 1261. Restorers scraped away Latin plaster, revealing iconic mosaics: Christ Pantocrator in the apex of the south-west vestibule and the Deësis (Christ flanked by Mary and John) above the Imperial Door—masterpieces of late Byzantine art.

Yet decades of neglect left roof leaks, prompting ad-hoc repairs that introduced exterior buttresses and crude timber bracing, signalling the empire’s waning coffers.

8. Ottoman Conquest & First Conversion to Mosque (1453 CE)

On 29 May 1453, Sultan Mehmed II (“the Conqueror”) prayed inside Hagia Sophia, declaring it Ayasofya Camii. To comply with Islamic practice, craftsmen erected a mihrab oriented toward Mecca, installed a minbar, and whitewashed figural mosaics. The call to prayer soon echoed from a hastily erected wooden minaret.

Hagia Sophia now served as the imperial Friday mosque, symbolizing continuity between Byzantine and Ottoman sovereignty. Christians were allowed limited worship in side chapels—an early sign of Istanbul’s multicultural tapestry.

9. Classical Ottoman Upgrades (1481 – 1739 CE)

Structural Mastery of Mimar Sinan

In the 16th century, master architect Mimar Sinan inspected cracks in the dome and designed massive exterior buttresses plus two elegant pencil-thin minarets. He also created the Hünkâr Mahfili (sultan’s loge) for private prayer. By reinforcing foundations with lead-lined iron cramps, Sinan preserved the church-mosque hybrid for another millennium.

Auxiliary Complex

Later sultans added:

- Mahmud I’s library (1739) in Baroque style

- Sultan’s mausoleums for Selim II, Murad III, Mehmed III, and their families

- A sıbyan mektebi (primary school) and imaret (soup kitchen) supplying daily meals

These annexes transformed Hagia Sophia into a külliye—an all-in-one Ottoman public service hub.

10. Fossati Brothers Restoration (1847 – 1849 CE)

Facing structural fatigue, Sultan Abdülmecid I invited Swiss-Italian architects Gaspare & Giuseppe Fossati. They:

- Installed 800 iron tie-rods for seismic stability.

- Uncovered, cleaned, then re-plastered mosaics—meticulously sketching them first (their drawings later aided 20th-century restorers).

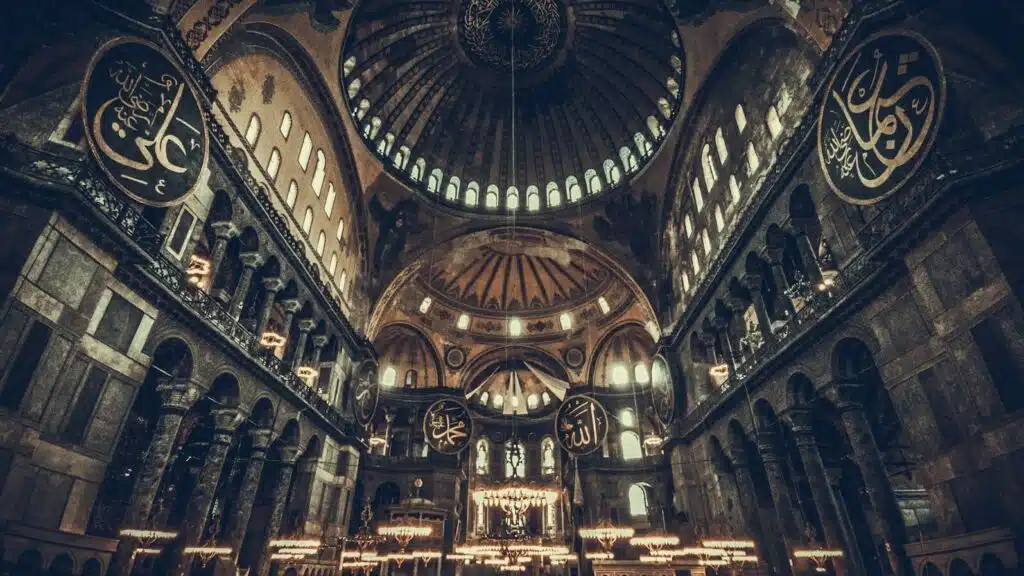

- Commissioned calligrapher Kazasker Mustafa Izzet to create eight 7.5-metre-diameter medallions bearing gilded names of Allah, Muhammad, and the first four caliphs—still among the world’s largest Arabic roundels.

The Fossati renovation entered Ottoman lore as proof that the empire could embrace Western technology without sacrificing Islamic identity.

11. Secularization & Museum Decree (1934 – 1935 CE)

Founding father Mustafa Kemal Atatürk pursued a secular republic. His Cabinet abolished Hagia Sophia’s mosque status on 24 November 1934, and, with Carnegie Foundation funds, American Byzantine scholar Thomas Whittemore led a team to peel away plaster from mosaics depicting Virgin Mary, archangels, and imperial couples like Constantine IX Monomachos & Empress Zoe.

On 1 February 1935 Hagia Sophia opened as Ayasofya Müzesı, framing Turkey as a bridge between Eastern and Western heritage during a precarious interwar era.

12. UNESCO World Heritage Listing (1985 CE)

Hagia Sophia, along with Topkapı Palace, Blue Mosque, and the Hippodrome, became part of the “Historic Areas of Istanbul” UNESCO listing.

This status galvanized global fundraising, enabling roof waterproofing, lead sheet replacement, and digital documentation of mosaics. It also helped craft a management plan balancing mass tourism (peaking at 3.7 million visitors in 2019) with conservation mandates—no small feat for a building sitting on seismic fault lines.

13. Long-Term Conservation Works (1993 – 2010 CE)

Over two decades, Turkish authorities and international partners:

- Injected epoxy into cracked piers

- Installed base-isolation bearings under critical columns

- Digitally mapped the dome with laser scanners, revealing deviations less than 75 mm—remarkable accuracy for 6th-century engineering

- Restored the Imperial Gate, whose oak panels still bear 10th-century bronze fittings

Conservators also introduced climate-control louvers to reduce condensation that threatened gold tesserae. These interventions illustrate the complex marriage of modern science and medieval craftsmanship.

14. Council of State Ruling & Second Conversion to Mosque (2020 CE)

On 10 July 2020 Turkey’s Council of State annulled the 1934 decree, ruling that Hagia Sophia’s waqf (endowment) stipulated perpetual mosque status. Hours later, a Presidential order reinstated daily Islamic prayers. UNESCO “took note with regret” but the government assured that mosaic curtains would open during visiting hours, entrance would remain free of charge, and non-Muslim guests were welcome outside prayer times. The first Friday prayer on 24 July 2020 drew thousands to Sultanahmet Square, echoing a 567-year continuum of worship.

15. Present Day: Dual Role & Visitor Etiquette (2020 – Present)

Mixed-Use Reality

Today, Hagia Sophia functions as Ayasofya-i Kebir Camii-Şerifi while retaining museum-style access. During five daily prayers, staff unfurl motorized blinds over icons like the Virgin Mary in the apse, then retract them afterward—an innovative compromise between Islamic aniconism and heritage display.

Practical Tips for 2025

| Topic | Quick Info |

|---|---|

| Entry Fee | Free, but donations welcome |

| Best Visit Window | 09:00–11:30 or 14:30–16:30 to avoid both prayer and cruise-ship crowds |

| Dress Code | Shoulders & knees covered; free headscarves available |

| Photo Policy | Allowed outside prayer; no flash or tripods |

| Audio Guides | Rent at kiosk or download the official app for AR overlays |

Key Takeaways

- Architectural Evolution: From Roman basilica to Byzantine domed masterpiece to Ottoman mosque, Hagia Sophia epitomizes syncretic design—link to your post on “Byzantine Architecture in Istanbul.”

- Political Mirror: Each conversion reflects regime change—connect to “Fall of Constantinople Explained.”

- Conservation Model: The building showcases global collaboration—cross-reference “UNESCO Sites in Turkey You Can’t Miss.”

In a single sweep of the centuries, Hagia Sophia tells a layered story of empire, faith, art, and resilience—cementing its place as not just a monument of stones and mosaics, but a living chronicle of human aspiration.